I fly a lot. Maybe not as much as some; I'm no "million miler", but I did fly approximately 100K miles last year, and have crossed 50K miles this year. In the world of things that cause unnecessary stress, boarding a plane is one of them. Everyone boards a little differently, and they all suffer from the same issues that leave the boarding process feeling inefficient and ripe for restructuring.

To understand the stage for boarding a plane, you need to understand where we're at now:

How many boarding groups is too many? Where each airline falls flat.

American has 10 boarding groups, Delta has 7, United has 6, and Southwest (for all intents and purposes) has 5. What I've found flying each dozens of times, is that most of them usually have "stacked" groups, wherein a disproportionate amount of passengers board in a single group, or too few in others.

A great example of this is Delta's Sky Priority group, which encompasses basically any semi-regular travel. On peak business flights (Monday mornings/ Thursday evenings), I'd venture that this Sky group is approximately a third of the plane.

American's new set of boarding groups creates a scenario where almost no one (occasionally a person of two) boards in Group 2, 6, or 8. As a gate agent, it can be a pain to call out so many boarding groups, and I've found that gate agents regularly group together 2, 3, and 4. As well as 6, 7, and 8. What this produces is a scenario which negates much of the status-earned group you're originally assigned to. What's the benefit of being in Group 2, if you're going to line up a clump of 2, 3, and 4 folks? American's system is far from ideal, but at least it's logical (e.g. starts with 1).

Delta, on the other hand, I've found is confusing for first time passengers. If your boarding pass says "Zone 1", the uninformed might assume that they are boarding first! Since Zone 1 is typically used for Comfort Plus seats, uninformed travelers regularly assume that the $30 extra they paid for their seat with 2" of extra leg room also affords them boarding first, whereas in reality, Zone 1 is actually the fourth group to board (behind pre-boarding, premium, and sky zones). This produces a situation where passengers regularly crowd the gate too early. "Sky" is usually overcrowded, like the Group 4 of American.

United isn't the best either. With a similar passenger stacking, Group 2 regularly includes up to a quarter of the whole plane. With that in mind, the very last person to Board in Zone 2 is just the same as first person to board in Zone 3. Although in truth, there's not much you can do about this. The one thing United does right, however, is they are sticklers for making sure you board in your group. Too often I've seen gate agents (of other airlines) shrug when passengers board out of order with no consideration to the rules that govern the rest of the passengers.

Southwest is one of the more interesting airlines. I'd noted they have 5 boarding groups (A1-15, A16-30, Families with Children, B1-60, C1-60). With the exception of the family section, everyone boards in order, so there is a much smaller range of benefits that is diminished relatively evenly with passengers (e.g. early passengers take the overhead bins and window/ aisle seats). Southwest's model is a "love it or hate it" thing. I float more into the latter camp, but that's a story for another day. Since you don't actually pick a seat until you board, there is significantly more incentive to want to board early (Southwest capitalizes on this with its "Early Bird" check-in), although once onboard, the only differentiation is largely just aisle, middle, or window. With the exception of the bulkheads, and two of the exit row seats, the seats are the same.

Net net - if you have too many boarding groups, you risk unintended consolidation and frustration from passengers (especially those in the later boarding groups, feeling like they're getting the short end of the stick). Whereas if you have too few groups, you risk negating the benefits provided to each group since you've minimized the differentiation between passengers. Not to mention in all of these scenarios, we haven't addressed how your seat choice influences your boarding order.

In recent years, United experimented with loading window passengers first, then middle seat, then aisles. In theory, it's a good idea since if everyone boarded this way (throwing out any pre-boarding, early boarding privileges), since you would never have to wait for someone to get out of their seat to slide in. Unfortunately in execution, it didn't succeed quite as planned, and united scraped it shortly after.

With that covered, let's consider the next challenge. What drives our behavior to board in a certain order?

Do you want to board first or last?

We're going to throw Southwest's "pick your seat" boarding out for the time being and assume that everyone has an assigned seat before they board. Based on that, in an ideal world, do you want to board first or last? Ideally last. Think about why people want to board a plane first: overhead bin space. Since your seat is reserved, but overhead bin space is not, the primary incentive of boarding early is to ensure you're able to snag a spot for your bag. Especially one that is near you and not many rows back.

If you didn't have to worry about bin space, the reasons to board early do not carry much weight: getting a cocktail/ drink early (only applies to first class), not having to wait in the jet bridge, sit down early, etc. Almost none of these as benefits, outweigh the inconvenience of having to check your bag after you've already boarded.

If bin space was reserved, the primary incentive to board early is materially minimized.

This is almost to the point that I'd venture you would create a more even distribution of when people want to board. The days of overcrowding the gate would disappear since there would be little incentive to board early since you'd already have that guarantee.

Let's check the numbers:

How many passengers can bring bags on board?

The most common plane is the US is the Boeing 737. Its 700 and 800 configurations make up about 18% of all commercial planes in the US[1]. As such, these planes were used as reference for some of these calculations.

| Airline | Plane | Seats | Bag Space | Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American | 737-800 | 160 (16 + 30 + 114) | ~100 bags | 63% |

| Delta | 737-700 | 124 (12 + 18 + 94) | ~70 bags | 57% |

| Delta | 737-800 | 160 (16 + 36 + 108) | ~100 bags | 63% |

| United | 737-700 | 126[2] | ~70 bags | 56% |

| United | 737-800 | 166[3] | ~100 bags | 60% |

| Southwest | 737-700 | 143[4] | ~70 bags | 49% |

| Southwest | 737-800 | 175[5] | ~100 bags | 57% |

| Avg: 58% |

-

Note that Utilization refers to the percentage of passengers (assuming a full flight) that will be able to utilize the overhead bins for their bags. The higher the percentage, the higher likelihood a passenger has of being able to find a space for their bag in the overhead bin space.

-

Note that Bag Space refers to an average of how many bags that aircraft can hold: 737-700 planes have 20 bins * 3.5 bags/ bin = 70 bags and 737-800 planes have 28 bins * 3.5 bags/ bin = ~100 bags. Each of these calculations already does not include 1 whole bin, which is typically reserved for safety equipment, or crew bags.

Key Takeaway: A little more than half of the passengers boarding a plane can put their bag in the overheard bin. More realistically, this number is actually lower across the board, since there is usually an issue with passengers:

- Bringing abnormally large bags that require them to be put in the bin horizontally (and thus taking the space of ~3 bags)

- Putting their backpack/ briefcase in the overhead bin instead of under the seat in front of them

- Placing their large coats in the bins (particularly during the Winter months).

Despite flight attendants reminding folks of these items, there is usually minimal enforcement, and sometimes passengers even engage in these activities maliciously (or strictly for their own benefit).

Sidenote: I once asked a passenger to move his backpack under the seat in front of him, wherein he refused, citing his height and that he needed the extra leg room. Needless to say, his "6' 2" frame" is the same as me, and I've never had an issue fitting in my seat.

Since it's about a 50/50 shot of getting overhead bin space for your bag, and with 3/4's of the US's major carriers charging for checked bags, it makes sense that an overwhelming majority of flights in the US include a battle for bag space. Throw in the convenience of not having to wait for your luggage, as well as wholly negating any possibility of a lost or damaged bag, it's not hard to understand why most folks prefer to carry on their bags.

That "battle" produces a heightened incentive to want to board first, which causes congestion at the gate, and increases the time to complete boarding while a good chunk of passengers will need to fight for bin space. This regularly includes passengers having to place their bag many rows behind them, then fight the current back upstream to get to their seat. I'd argue this part of the boarding process is one of the most inefficient and contributes sizable amount of avoidable delays due to boarding.

Since finding bin space is a material contributor to boarding slowdowns, lets correct the bag issue.

How much is overhead bin space worth?

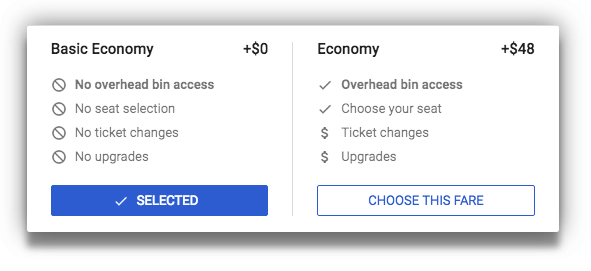

We've started to see airlines roll out their "basic" ticket packages that only allow you to bring a bag that'll fit under the seat in front of you. In American's case, the roll-out of that tier didn't actually reduce prices, but raised most other fare classes to compensate for the deficit that the "basic" ticket provides. Nonetheless, American and United charge approximately $40 - $50 for a roundtrip ticket to "upgrade" out of the that basic class. Here's what you get for those extra funds:

- Access to overhead bin space

- An ability to pick your seat prior to boarding (within reason)

- An ability to change tickets (fly standby, etc)

- Eligible for upgrades (with proper status)

The last three items on this list are what I could consider "givens", or standard options provided by airlines. Since all four of the major US carriers are not classified as budget carriers, they are simply not setup logistically (or otherwise) to operate the same way budget carriers do. In that they do have not have near the flexibility to "piece out" components of the flight like budget carriers can do.

With that in mind, lets approximate that 50% of the ticket hike can be attributed to being provided (or rather the right, but not the guarantee) the access to an overhead bin (a generous overstatement of the value of the other "benefits"). Therefore we might say that you're effectively paying (or receiving the benefit of) $10-$12 to place your bag in an overhead bin each way[6]. Given that checking a bag altogether runs about a minimum of $50, this is seemingly reasonable. Especially given you're making an airlines job easier (no additional screening, loading, and unloading; not to mention the write off's that lost or damaged bag claims create each day).

So if you start to associate a cost with this benefit, you'll have a supply and will need to balance it with demand. Since supply will always be fixed, you'd need to control demand to most accurately match. As today there's effectively uncapped demand, almost every single flight deals with this issue of "first come, first serve", which again produces unneeded stress as passengers wrestler for their place in the boarding line.

Since finding bin space is a material contributor to boarding slowdowns, lets correct the bag issue.

Can you reserve bin space?

This is one of the more interesting questions that I don't think airlines have truly considered. The model in the industry is almost ubiquitously uncontrolled space, so putting the process in place to reserve these spaces would require some process changes, potentially cosmetic/ hardware, education to the consumer, and deeper integration with ticketing and frequent flier accounts.

If you've been on plane recently, you might have noticed that the "economy plus" section typically has signage that indicate that it's reserved for those customers. While I've never seen this actually enforced, this is a rather mundane and undeveloped approach to handling bin space. There are still no guarantees that you as an "Main Cabin Extra" (or what have you), will have bin space. Though it's unlikely you'll have an issue if you board early enough.

Another thought might be to install dividers or fins into the bin space. While retrofitting an entire fleet would be costly, you'd provide a very easy way to make sure a passenger only uses their space. With a relevant identifier (e.g. Bin 2C), you've provided an avenue to allow space to individually reserved.

However the better answer seems to be, why not simply refer to the whole bin as a spot? Since we know how many bags should fit, you would simply provide each passenger with an assigned bin number to use. Of course, for this to succeed, you need two primary items:

- Good enforcement. Like reserved parking spaces, you'd need to make sure passengers don't abuse the right to a bin and choose a bin that isn't there's. Especially since airlines won't be able to always match a bin space with a passenger, there may be cases where a self-centered passenger may be inclined to take a bin that isn't there's - even if they've been assigned one.

- There needs to be more consistent and stronger adherence to approved bag sizes. Since this approach relies on almost precise bag sizes and aircraft bin sizes, allowing passengers to bring oversized bags would disrupt the order and create a chain-event of issues that would threaten to materially lengthen the boarding process.

But there is one last piece of the puzzle.

With a limited supply, how do we balance demand?

Can you incentive passengers to not use the overhead bin space?

We spoke earlier about how the value of access to the overhead bin space is approximately $10. While I'm sure airlines would love to slap an extra $10 on everyone's ticket to use the overhead bin, you'd likely create an even bigger problem as gate-checking a bag would likely become all too common, which would increase the demand on ground crews, without the typical cost benefits that come from checking a bag prior to security. It could be easy to simply tack on a fee for gate-checked bags like so many budget airlines do, but this is likely to frustrate the average customer.

With that being said, I think flight prices are dynamic enough that a long term approach could entail including the right to a bin, directly on to a ticket. Afterall, every ticket in the US has included a $5.60 fee to support airport security. Even when booking flights with miles, you still have to pay that fee. I'd argue it's largely underutilized (or rather misappropriated) funds, but that is neither here nor there.

More near term, I think airlines could approach the problem differently.

- For all existing status tiers and first class members, include guaranteed space to a bin. If they don't need it, offer them miles to skip bin access. After all, status and first class members already can check bags free. If you provide them more incentive to not bring their bag on the plane, they might very well take you up on it. Since each flight effectively generates thousands of miles credited to frequent flier members, I have to imagine the cost of handling out additional miles in small chunks would be almost negligible in the perceived cost to the airline.

- The beauty here is that you don't have to earn miles at the same rate by which you spend them. In that I mean an average flight might earn you (with no status), 1000 miles. Based on a valuation of say 1.5 cents/ miles, you've just earned $15 worth of rewards. We spoke earlier that the value of a bin is likely worth $10, but since you'd want to keep earning proportional to that of the flight itself, you could provide passengers an extra 100 or 200 miles to skip overhead bin space and it'd likely be well received, and that's an easy 10% - 15% boost in earning! Not to mention, those 100 miles will only cost the airline a few dollars, max. Just like with hotel loyalty programs, you can usually receive a sizeable credit for skipping housekeeping for a night. The same premise applies here. It's a win-win really.

But what about for passengers who aren't frequent fliers or don't have interest in miles?

- Provide credit for a free cocktail or snack

- Lots of airlines do this as gestures for a variety of reasons. For example, Delta regularly adds coupons to frequent flier accounts, wherein Southwest regularly mails stacks of four to passengers (no status included), likely as a way to encourage their next flight. The cost of a cocktail or snack-box is likely very low to the airline itself, but the perceived benefit is much greater. Offering passengers a simple coupon for a drink or snack in exchange not using overhead bin space is a simple, cost-effective way (with a high perceived value) to lessen demand.

- Give them a discount or wave the fee associated with checking a bag altogether

- Since passengers already have an expectation that they can bring a bag onboard, there are many angles airlines could take to subsidize the value of a bag to be checked. For example, if airlines started asking you to disclose your carry-on baggage during check-in (and let's reasonably assume that passengers are smart enough to know the difference between checked luggage and carry-on luggage in this case primarily being size), an airline could forecast demand well before passengers board. Consider that over time, airlines could produce models that forecast exactly how much demand they expect (in terms of demand for overhead bin space) for each flight.

- Just as airlines have complex predictive models for forecasting demand for the seats on a plane (in order to maximize revenue from cancellations, etc), the data from this model would allow an airline to very reasonably minimize the amount of incentives they need to provide to passengers. For example, if a well-trained model estimated that only 50% of the passengers on a plane were likely to carry a bag onboard, there is little reason for an airline to hand out incentives (such as miles, drink coupons, or bag check discounts) if they don’t need to. Whereas in the model returned something like 90%, the airline knows it would need to aggressively work to correct demand through incentives such as the above.

- Since passengers already have an expectation that they can bring a bag onboard, there are many angles airlines could take to subsidize the value of a bag to be checked. For example, if airlines started asking you to disclose your carry-on baggage during check-in (and let's reasonably assume that passengers are smart enough to know the difference between checked luggage and carry-on luggage in this case primarily being size), an airline could forecast demand well before passengers board. Consider that over time, airlines could produce models that forecast exactly how much demand they expect (in terms of demand for overhead bin space) for each flight.

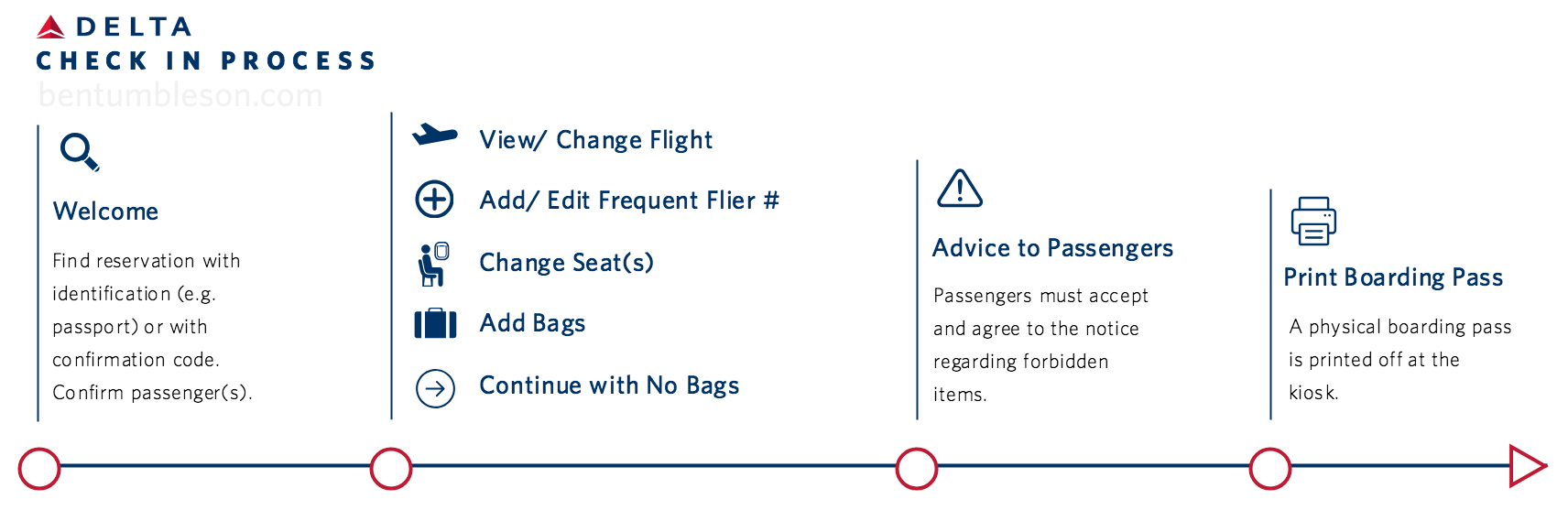

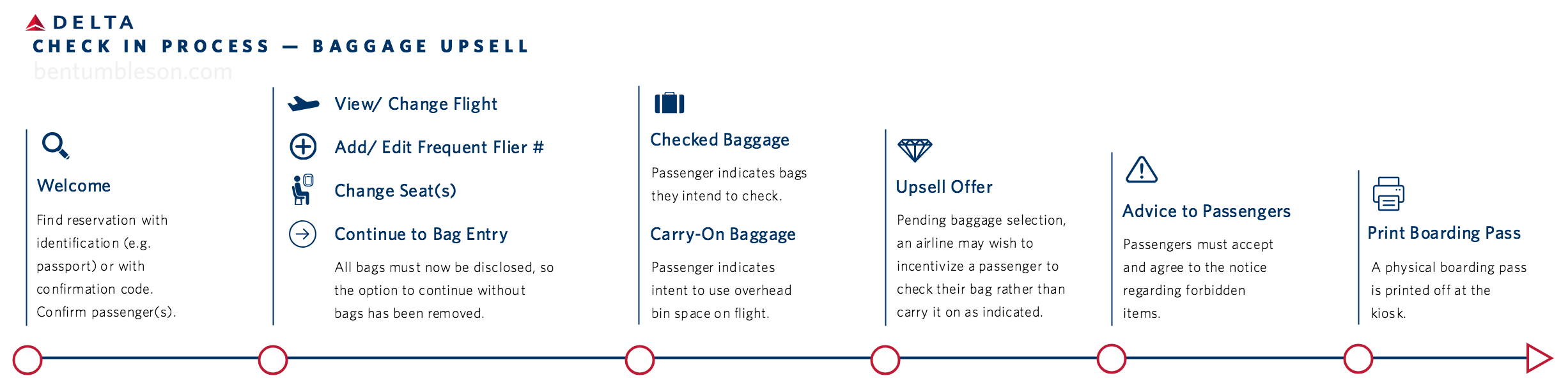

As a related note, there is huge opportunity to train customers and set expectations regarding the likelihood of being able to bring a bag. What I’ve regularly seen flying is most gate agents will instinctively recommend to passengers in the later boarding groups that they may be required to check their bag as the likelihood of overhead bin space being available is near zero by the time they can expect to board. If airlines were to extend this knowledge to the check-in process, the “upsell” of recommending passengers check their bag is much easier. For example, if a passengers has to go to kiosk in the airport to get their boarding pass (they haven’t checked in online or via their phone), then depending on their boarding group, how many passengers are expected on the flight, and an estimation of how many bags can be accommodated, and airline could make an immediate upsell to have passengers that might not have otherwise checked their bags, check them.

To help illustrate this example, I've put together a high level process flow that explains what the check-in process at Delta airport kiosk looks like. Note that this process is almost identical to passengers who complete check-in on their mobile phones, with the exception being that the boarding pass is digitially loaded on the phone.

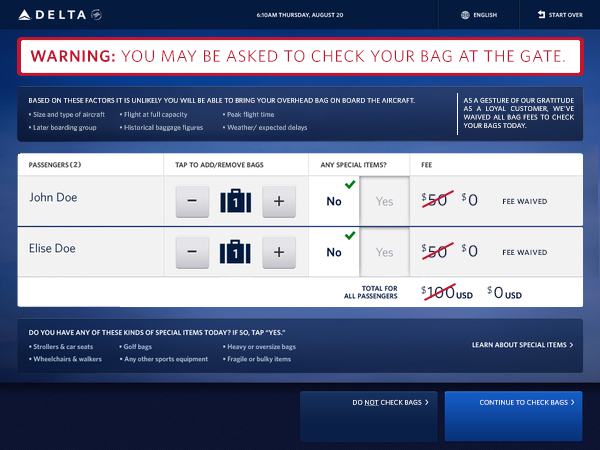

Example: A family of four

Take an not all to unrealistic scenario of a family of four traveling for an annual holiday. The cost-conscious parents instruct the whole family they are only to have carry on bags to avoid having to check bags (and add an extra $200 in costs each way). In this example, this family still might be in one of the last boarding groups on a full flight (say to a popular beach destination). While checking in the family, the airline can offer the whole family the convenience of checking all of their bags free. In this example, the check-in process could make a reasonable assumption that because the family is already planning on bringing the bags on board, paired with the full flight, and a high likelihood (given their boarding group), that they will be forced to gate check all their bags. And as such, the check in kiosk can present this as a warning, with the recommended mitigation of checking all of their bags now, free of charge.

In our example, an airline can note that this is not lost revenue, since this family had no intention of checking their bags anyway. And by checking the bags now, you’ve eased the logistical challenges of gate checking a bag, increased the convenience of the family, while leaving them satisfied with a presumed savings of over $200!

Conclusion

Boarding an airplane is consistently a difficult process regardless of what airline you're on. While airlines have worked to manipulate the way in which customers get their seats in an effort to speed up boarding time, little emphasis has been placed on how carry-on baggage affects the boarding process.

I would venture that as airlines continue to experiment with overhead bin space and access, they'll find that this is directly related to the desire to board a plane first, which in term affects the speed and efficiency in which an aircraft can be fully boarded. In a basic implementation, I propose that airlines began assigning overhead bin space just as they do seats. With enough data, the likelihood of having to have passengers gate check their bags, board with a bag for which there is no space, or have to place their overhead bag many rows behind him upon boarding, will continue to shrink, leading to an expedited boarding process to the benefit of all.

http://www.fi-aeroweb.com/US-Commercial-Aircraft-Fleet.html ↩︎

United has three different versions of the 737-700 that seat 136, 124, and 118. And average of 126 was used. ↩︎

United has four different versions of the 737-800, wherein V1 seats 154, with V2, V3, and V4 all seating 166 passengers total. ↩︎

Southwest flights do not have a separation of cabins - all seats are standard economy. ↩︎

Southwest flights do not have a separation of cabins - all seats are standard economy. ↩︎

Please don't quote me on this. It's strictly an approximation based on the relative price differences of different fare classes. ↩︎

Member discussion: